The goal of quickr is to make your R code run quicker.

R is an extremely flexible and dynamic language, but that flexibility and dynamicism can come at the expense of speed. This package lets you trade back some of that flexibility for some speed, for the context of a single function.

The main exported function is quick(), here is how you

use it.

library(quickr)

convolve <- quick(function(a, b) {

declare(type(a = double(NA)),

type(b = double(NA)))

ab <- double(length(a) + length(b) - 1)

for (i in seq_along(a)) {

for (j in seq_along(b)) {

ab[i+j-1] <- ab[i+j-1] + a[i] * b[j]

}

}

ab

})quick() returns a quicker R function. How much quicker?

Let’s benchmark it! For reference, we’ll also compare it to a pure-C

implementation.

slow_convolve <- function(a, b) {

declare(type(a = double(NA)),

type(b = double(NA)))

ab <- double(length(a) + length(b) - 1)

for (i in seq_along(a)) {

for (j in seq_along(b)) {

ab[i+j-1] <- ab[i+j-1] + a[i] * b[j]

}

}

ab

}

library(quickr)

quick_convolve <- quick(slow_convolve)

convolve_c <- inline::cfunction(

sig = c(a = "SEXP", b = "SEXP"), body = r"({

int na, nb, nab;

double *xa, *xb, *xab;

SEXP ab;

a = PROTECT(Rf_coerceVector(a, REALSXP));

b = PROTECT(Rf_coerceVector(b, REALSXP));

na = Rf_length(a); nb = Rf_length(b); nab = na + nb - 1;

ab = PROTECT(Rf_allocVector(REALSXP, nab));

xa = REAL(a); xb = REAL(b); xab = REAL(ab);

for(int i = 0; i < nab; i++) xab[i] = 0.0;

for(int i = 0; i < na; i++)

for(int j = 0; j < nb; j++)

xab[i + j] += xa[i] * xb[j];

UNPROTECT(3);

return ab;

})")

a <- runif (100000); b <- runif (100)

timings <- bench::mark(

r = slow_convolve(a, b),

quickr = quick_convolve(a, b),

c = convolve_c(a, b),

min_time = 2

)

timings

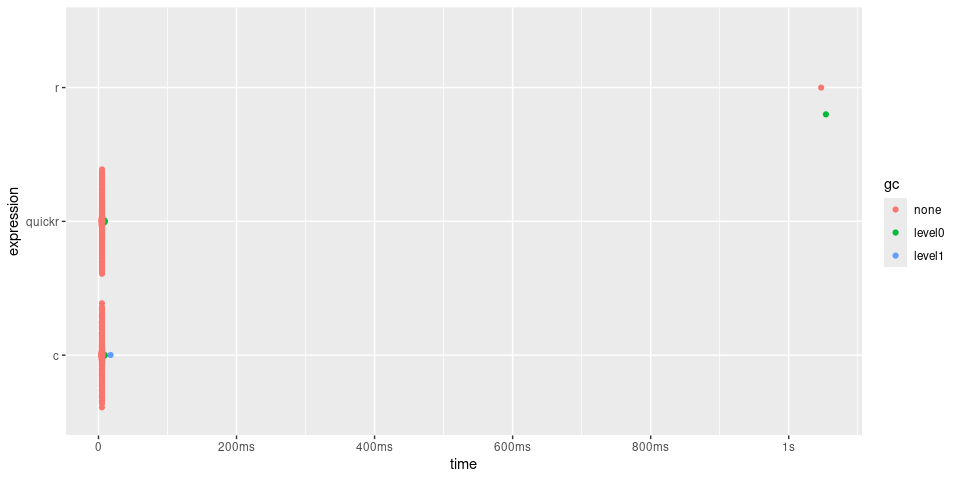

#> # A tibble: 3 × 6

#> expression min median `itr/sec` mem_alloc `gc/sec`

#> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> <bch:tm> <dbl> <bch:byt> <dbl>

#> 1 r 1.04s 1.04s 0.957 782KB 0.957

#> 2 quickr 4.85ms 5.03ms 198. 782KB 3.61

#> 3 c 4.88ms 5.06ms 197. 782KB 4.13

plot(timings) + bench::scale_x_bench_time(base = NULL)

In the case of convolve(), quick() returns

a function approximately 200 times quicker, giving similar

performance to the C function.

quick() can accelerate any R function, with some

restrictions:

declare().integer, double, logical, and

complex.NA values are not supported.#> [1] - : != ( [ [<- {

#> [8] * / & && %/% %% ^

#> [15] + < <- <= = == >

#> [22] >= | || Arg Conj Fortran Im

#> [29] Mod Re abs acos as.double asin atan

#> [36] break c cat cbind ceiling character cos

#> [43] declare dim double exp floor for if

#> [50] ifelse integer length log log10 logical matrix

#> [57] max min ncol next nrow numeric print

#> [64] prod raw repeat runif seq sin sqrt

#> [71] sum tan which.max which.min whileMany of these restrictions are expected to be relaxed as the project matures. However, quickr is intended primarily for high-performance numerical computing, so features like polymorphic dispatch or support for complex or dynamic types are out of scope.

declare(type()) syntax:The shape and mode of all function arguments must be declared. Local and return variables may optionally also be declared.

declare(type()) also has support for declaring size

constraints, or size relationships between variables. Here are some

examples of declare calls:

declare(type(x = double(NA))) # x is a 1-d double vector of any length

declare(type(x = double(10))) # x is a 1-d double vector of length 10

declare(type(x = double(1))) # x is a scalar double

declare(type(x = integer(2, 3))) # x is a 2-d integer matrix with dim (2, 3)

declare(type(x = integer(NA, 3))) # x is a 2-d integer matrix with dim (<any>, 3)

# x is a 4-d logical matrix with dim (<any>, 24, 24, 3)

declare(type(x = logical(NA, 24, 24, 3)))

# x and y are 1-d double vectors of any length

declare(type(x = double(NA)),

type(y = double(NA)))

# x and y are 1-d double vectors of the same length

declare(

type(x = double(n)),

type(y = double(n)),

)

# x and y are 1-d double vectors, where length(y) == length(x) + 2

declare(type(x = double(n)),

type(y = double(n+2)))viterbiThe Viterbi algorithm is an example of a dynamic programming

algorithm within the family of Hidden Markov Models (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viterbi_algorithm). Here,

quick() makes the viterbi() approximately 50

times faster.

slow_viterbi <- function(observations, states, initial_probs, transition_probs, emission_probs) {

declare(

type(observations = integer(num_steps)),

type(states = integer(num_states)),

type(initial_probs = double(num_states)),

type(transition_probs = double(num_states, num_states)),

type(emission_probs = double(num_states, num_obs)),

)

trellis <- matrix(0, nrow = length(states), ncol = length(observations))

backpointer <- matrix(0L, nrow = length(states), ncol = length(observations))

trellis[, 1] <- initial_probs * emission_probs[, observations[1]]

for (step in 2:length(observations)) {

for (current_state in 1:length(states)) {

probabilities <- trellis[, step - 1] * transition_probs[, current_state]

trellis[current_state, step] <- max(probabilities) * emission_probs[current_state, observations[step]]

backpointer[current_state, step] <- which.max(probabilities)

}

}

path <- integer(length(observations))

path[length(observations)] <- which.max(trellis[, length(observations)])

for (step in seq(length(observations) - 1, 1)) {

path[step] <- backpointer[path[step + 1], step + 1]

}

out <- states[path]

out

}

quick_viterbi <- quick(slow_viterbi)

set.seed(1234)

num_steps <- 16

num_states <- 8

num_obs <- 16

observations <- sample(1:num_obs, num_steps, replace = TRUE)

states <- 1:num_states

initial_probs <- runif (num_states)

initial_probs <- initial_probs / sum(initial_probs) # normalize to sum to 1

transition_probs <- matrix(runif (num_states * num_states), nrow = num_states)

transition_probs <- transition_probs / rowSums(transition_probs) # normalize rows

emission_probs <- matrix(runif (num_states * num_obs), nrow = num_states)

emission_probs <- emission_probs / rowSums(emission_probs) # normalize rows

timings <- bench::mark(

slow_viterbi = slow_viterbi(observations, states, initial_probs,

transition_probs, emission_probs),

quick_viterbi = quick_viterbi(observations, states, initial_probs,

transition_probs, emission_probs)

)

timings

#> # A tibble: 2 × 6

#> expression min median `itr/sec` mem_alloc `gc/sec`

#> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> <bch:tm> <dbl> <bch:byt> <dbl>

#> 1 slow_viterbi 147.12µs 162.33µs 5957. 1.59KB 16.8

#> 2 quick_viterbi 2.48µs 2.62µs 367468. 0B 0

plot(timings)

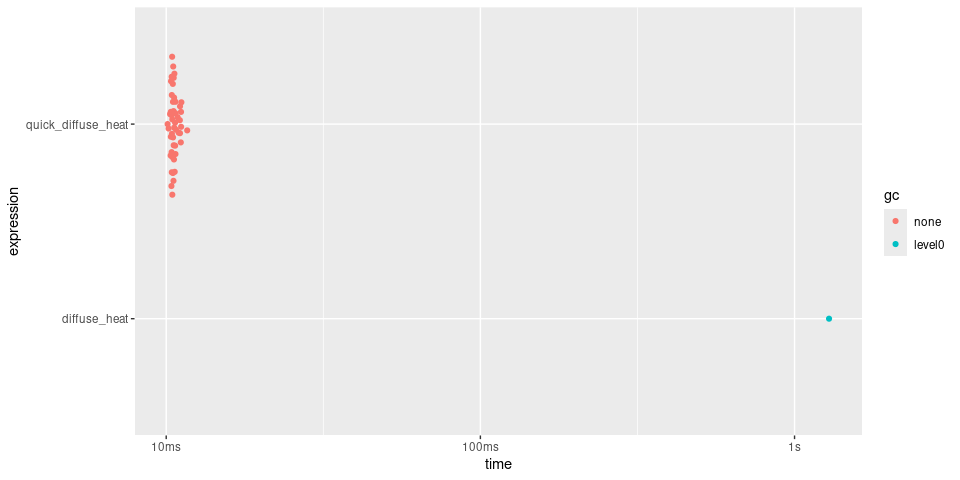

Simulate how heat spreads over time across a 2D grid, using the finite difference method applied to the Heat Equation.

Here, quick() returns a function over 100 times

faster.

diffuse_heat <- function(nx, ny, dx, dy, dt, k, steps) {

declare(

type(nx = integer(1)),

type(ny = integer(1)),

type(dx = integer(1)),

type(dy = integer(1)),

type(dt = double(1)),

type(k = double(1)),

type(steps = integer(1))

)

# Initialize temperature grid

temp <- matrix(0, nx, ny)

temp[nx / 2, ny / 2] <- 100 # Initial heat source in the center

# Time stepping

for (step in seq_len(steps)) {

# Apply boundary conditions

temp[1, ] <- 0

temp[nx, ] <- 0

temp[, 1] <- 0

temp[, ny] <- 0

# Update using finite differences

temp_new <- temp

for (i in 2:(nx - 1)) {

for (j in 2:(ny - 1)) {

temp_new[i, j] <- temp[i, j] + k * dt *

((temp[i + 1, j] - 2 * temp[i, j] + temp[i - 1, j]) /

dx ^ 2 + (temp[i, j + 1] - 2 * temp[i, j] + temp[i, j - 1]) / dy ^ 2)

}

}

temp <- temp_new

}

temp

}

quick_diffuse_heat <- quick(diffuse_heat)

# Parameters

nx <- 100L # Grid size in x

ny <- 100L # Grid size in y

dx <- 1L # Grid spacing

dy <- 1L # Grid spacing

dt <- 0.01 # Time step

k <- 0.1 # Thermal diffusivity

steps <- 500L # Number of time steps

timings <- bench::mark(

diffuse_heat = diffuse_heat(nx, ny, dx, dy, dt, k, steps),

quick_diffuse_heat = quick_diffuse_heat(nx, ny, dx, dy, dt, k, steps)

)

#> Warning: Some expressions had a GC in every iteration; so filtering is

#> disabled.

summary(timings, relative = TRUE)

#> Warning: Some expressions had a GC in every iteration; so filtering is

#> disabled.

#> # A tibble: 2 × 6

#> expression min median `itr/sec` mem_alloc `gc/sec`

#> <bch:expr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 diffuse_heat 131. 127. 1 1011. Inf

#> 2 quick_diffuse_heat 1 1 127. 1 NaN

plot(timings)

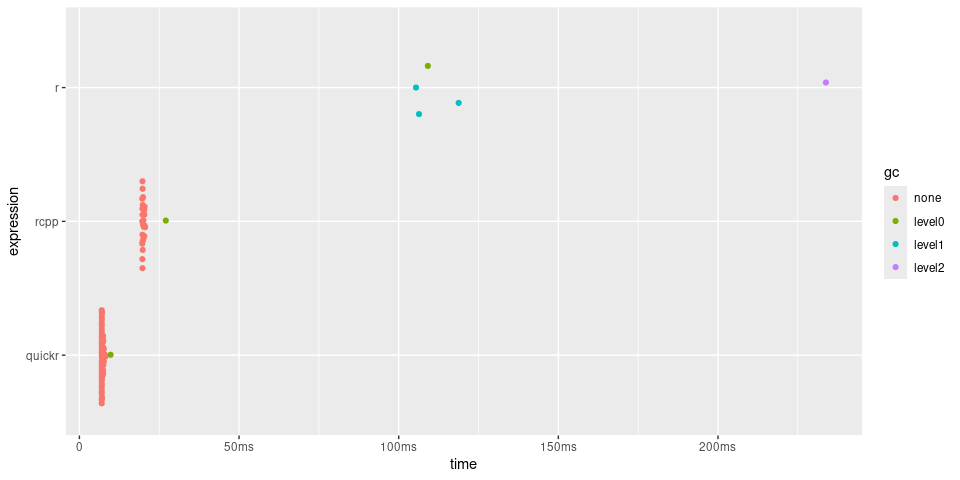

Here is quickr used to calculate a rolling mean. Note that the CRAN package RcppRoll already provides a highly optimized rolling mean, which we include in the benchmarks for comparison.

slow_roll_mean <- function(x, weights, normalize = TRUE) {

declare(

type(x = double(NA)),

type(weights = double(NA)),

type(normalize = logical(1))

)

out <- double(length(x) - length(weights) + 1)

n <- length(weights)

if (normalize)

weights <- weights/sum(weights)*length(weights)

for(i in seq_along(out)) {

out[i] <- sum(x[i:(i+n-1)] * weights) / length(weights)

}

out

}

quick_roll_mean <- quick(slow_roll_mean)

x <- dnorm(seq(-3, 3, len = 100000))

weights <- dnorm(seq(-1, 1, len = 100))

timings <- bench::mark(

r = slow_roll_mean(x, weights),

rcpp = RcppRoll::roll_mean(x, weights = weights),

quickr = quick_roll_mean(x, weights = weights)

)

#> Warning: Some expressions had a GC in every iteration; so filtering is

#> disabled.

timings

#> # A tibble: 3 × 6

#> expression min median `itr/sec` mem_alloc `gc/sec`

#> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> <bch:tm> <dbl> <bch:byt> <dbl>

#> 1 r 114.2ms 132.75ms 5.66 124.24MB 9.44

#> 2 rcpp 19.35ms 19.58ms 50.9 4.44MB 0

#> 3 quickr 6.73ms 6.87ms 142. 781.35KB 1.98

timings$expression <- factor(names(timings$expression), rev(names(timings$expression)))

plot(timings) + bench::scale_x_bench_time(base = NULL)

quickr in an R

packageWhen called in a package, quick() will pre-compile the

quick functions and place them in the ./src directory. Run

devtools::load_all() or

quickr::compile_package() to ensure that the generated

files in ./src and ./R are in sync with each

other.

In a package, you must provide a function name to

quick(). For example:

my_fun <- quick(name = "my_fun", function(x) ....)You can install quickr from CRAN with:

install.packages("quickr")You can install the development version of quickr from GitHub with:

# install.packages("pak")

pak::pak("t-kalinowski/quickr")You will also need a C and Fortran compiler, preferably the same ones used to build R itself.

On macOS:

Make sure xcode tools and gfortran are installed, as described in https://mac.r-project.org/tools/. In Terminal, run:

sudo xcode-select --install

# curl -LO https://mac.r-project.org/tools/gfortran-12.2-universal.pkg # R 4.4

curl -LO https://mac.r-project.org/tools/gfortran-14.2-universal.pkg # R 4.5

sudo installer -pkg gfortran-12.2-universal.pkg -target /On Windows:

On Linux: